Shortly after I joined my current employer as a cloud engineer, I was invited to participate in the AWS Cloud Warrior program, circa 2016. This was introduced as the AWS program for the best engineers in the AWS partner community, and its inception in Australia meant that it was filled with many significant people in the ecosystem that I knew from my time as one of the first Solution Architects for AWS in Australia & New Zealand.

This program aimed to have these senior engineers collaborate on cloud improvements, as well as engaging those engineers who sought to educate the wider (public) cloud community on how to achieve best practice. It encouraged this collaboration by routinely holding gatherings for the engineers in face-to-face meetings. AWS would fund domestic travel and accommodation, and bring service team members for various AWS Cloud Services to these gatherings. This was the partner community’s chance to provide direct feedback in a workshop-like environment on the improvements and limitations that were being experienced in the real-world, delivering and managing solutions for clients.

Key observations included long-term operations and supportability, continual security uplift, and removing the undifferentiated heavy lifting our form the client responsibility, and behind the dividing line of the Cloud services. This in turn reduced the cost to the end clients, across the board.

The benefits to AWS were huge. The service improvements were significant in the way that cloud was being shaped.

I was fortunate enough that my employer would fund my time to participate.

As a result, many ways to implement, scale and operate digital solutions in Cloud were championed by the Warrior community, who took to blogging, running user groups, and other activities to share this best practice and set the bar high for delivery across the entire global cloud engineering community.

This program got rolled over into the Ambassador program, and expanded to include the rest of the world. The ‘contributions‘ that the participants made were then tracked though a portal for the Ambassadors to submit to, with a simple gamification to encourage participation even further. The reward for this was an annual Ambassador Summit event, held face to face in Seattle, with flights and accommodation covered by Amazon.

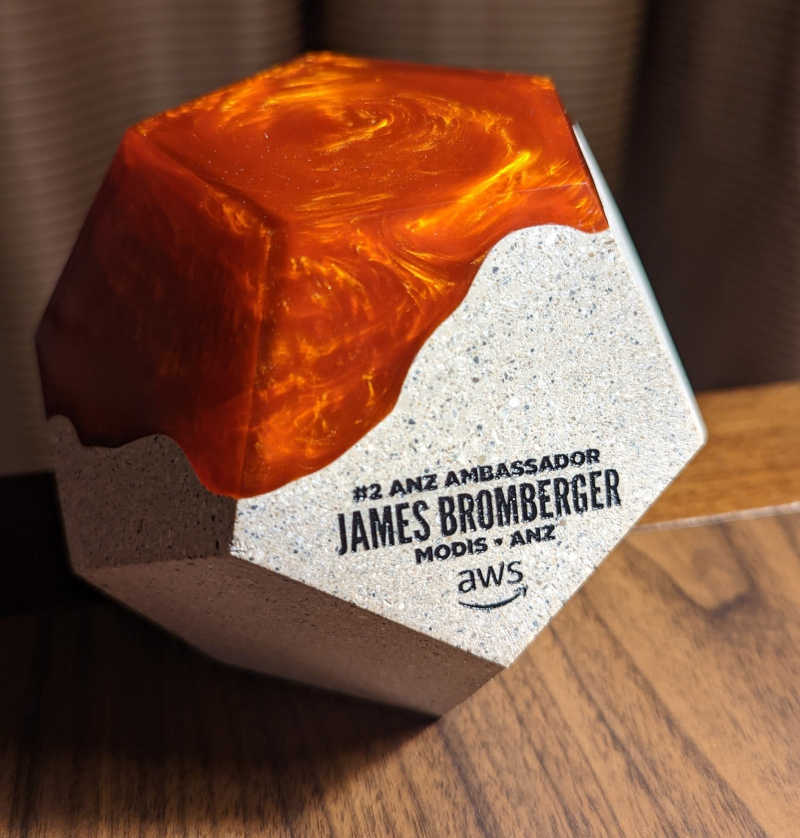

I attended this several times, based on the body of blog submissions and community contributions I had made, and was racked #2 Ambassador in Australia and New Zealand for several years.

Again my time was gratefully funded by my employer to participate. These learnings were obviously shared deeply within the technical community within my employer, and over time, several of my colleagues also then joined me in this program, having met the eligibility requires. It was a point of differentiation to claim that my employer had multiple individuals in the AWS Ambassador program.

Then came the change. It wasn’t heralded, but felt. The Australian-domestic Ambassador meetings ceased. The funding for the Global Summit reduced to no longer covering flights to Seattle, but my employer was good enough to cover this for a year.

The following year, no funding at all was available for flights or accommodation, which made this impossible to participate from Australia.

Access to re:Invent, the global cloud conference in Las Vegas, continued as a complementary ticket to attend – but never with flights or accommodation cover.

Despite all of the benefits drying up, remaining in the program required the continuous investment in community support and education activities by the participants.

I looked to the AWS Ambassador program as being the equivalent of a Distinguished Engineer, or Most Valuable Professional as seen with other vendor ecosystems, but AWS had disengaged this demographic that had helped shape their platform.

Questions were asked regularly of the AWS team assigned (which turned over several times) about what was happening to the program. No answers that instilled confidence were shared.

I found I was explaining the existence and value of the program far more than AWS would; none of my global clients knew there was such a group of senior engineers that we were a part of, and so the entire value evaporated.

When the consulting services partner has to introduce and explain the vendors’ recognition program to the client, something is wrong. This was further highlighted multiple times with the lack of mention of ambassadors at the AWS Summits, replaced with the wide Community Heroes program.

I continued to participate in the program, but there was no interaction, no feedback, and no events across A/NZ since around 2023. Then at the end of 2024, I stopped submitting the cloud blog posts I authored into the portal. I wanted to see if would happen, what contact would be initiated.

The answer: Nothing.

Last week I found that I was no longer listed in the Ambassador portal. With no contact, no emails, no notice.

10 years: 2016 – 2025.

Will it change my blogging? Well, I’m much less at the coal-face these days, running a global practice in 14 countries. My focus for a long time has not been on my own delivery and training, but that of 1,800 other AWS cloud capable staff that I work with, for them to be at a level of capability that reduces risk and improves value to clients. This is how I scale myself.

I shared a lot of my perspectives with the other Ambassadors and AWS Service teams, and they shared with me. Rowan, Arjen, Ian, Cristian, Elliot and many more in this group across A/NZ: thank you for your insights and perspectives.

As an ex-AWS employee (one of the first few AWS Solution Architects in Australia, see my CV), I am disappointed and somewhat embarrassed at the way this program has been handled for the last few years as it was defunded and provided less value to the participants.

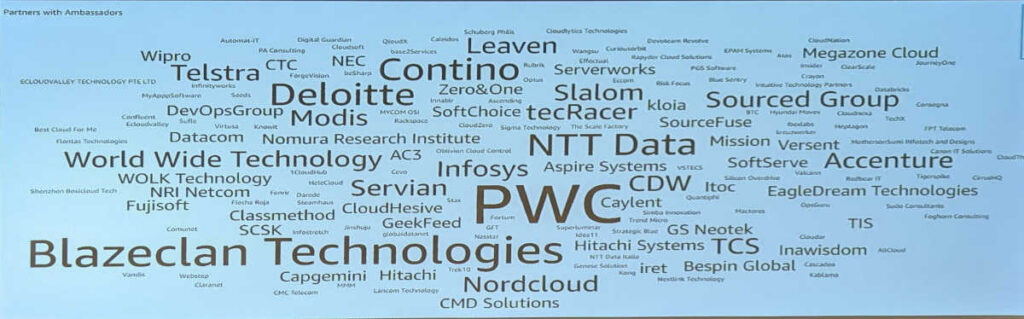

For interest, this is what this community looked like in 2022 at the Ambassador Summit in Seattle, with the size of the text reflecting the number of Ambassadors:

Some names have changed, some have gone away, and there are likely some new ones now.